Rev. Dr. Virgil Alexander Wood, a trusted mentor, church leader, educator, and towering figure in the civil rights movement, passed away on December 28, 2024, at the age of 93.

I had the privilege of knowing Dr. Wood during what he warmly referred to as his “twilight years.” We first connected in 2016, after he called me about a video I created for a MacArthur 100&Change proposal. I’ll say more about this video and why it led to a close partnership and friendship below.

Dr. Wood’s life was a testament to faith, resilience, and a deep commitment to social justice. Ordained as a Baptist minister in his late teens, he served churches for over five decades in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Virginia. While pastoring in Lynchburg, Virginia, he became deeply involved in the civil rights movement, establishing the Lynchburg Improvement Association as a local arm of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

From 1963 to 1970, he led the Blue Hill Christian Center in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood and chaired the Massachusetts Unit of the SCLC. As a close confidant of Dr. King, Jr., he served on the SCLC’s National Executive Board during the final ten years of Dr. King, Jr’s. life, coordinating the State of Virginia’s involvement in the historic March on Washington in 1963.

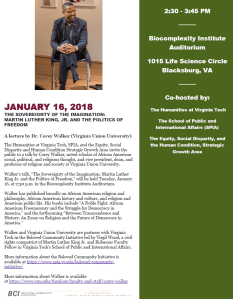

Dr. Wood’s academic achievements reflected his thirst for knowledge and passion for empowering others. After earning a BA in history from Virginia Union University in 1952, he obtained a Master of Divinity from Andover Newton Theological School in 1956 and a Doctorate in Education from Harvard University in 1973. His career in education was as impactful as his ministry, with roles as Dean and Director of the African American Institute at Northeastern University and as a professor at Virginia Seminary and College. He also served as a lecturer and researcher at Harvard University and led the Beloved Community Initiative as a Distinguished Ridenour Faculty Fellow in the School of Public and International Affairs at Virginia Tech.

Dr. Wood’s dedication to economic justice led him to work as an administrator for the Opportunities Industrialization Centers (OICs) of America, founded by his friend and mentor Dr. Leon Sullivan to provide job training for underserved communities. Dr. Wood established 13 OICs in eight southern states and in Boston, Massachusetts. He also lent his wisdom to three White House Conferences under the Johnson, Nixon, and Carter administrations.

Throughout his life, Dr. Wood maintained friendships with civil rights icons such as Rosa Parks, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Sr., Dr. Leon Sullivan, Dr. Ralph Abernathy, Dr. Samuel Dewitt Proctor, Dr. C.T. Vivian, Dr. Wyatt Tee Walker, and many others. Some of these connections can be seen in Dr. Wood’s 2020 book entilted In Love We Still Trust: Lessons we learned from Martin Luther King Jr. and Sr.

When we first met in person, I remember we joked that if I lived my life twice over, I’d still be younger than him. It was a lighthearted moment that underscored the incredible tenure of his life’s work, his wealth of wisdom, and his generous spirit.

Our work together built on my long-term collaboration with Prof. Robert Ashford, who has been advancing Louis Kelso’s theory of binary economics throughout his academic career. The 90-second 100&Change video mentioned above outlined a proposal to provide citizens of a country with a capital ownership stake in their nation’s economic future. Using the principles of binary economics, people could acquire capital (i.e., an ownership stake in new and inherently sustainable goods and services) with credit repayable with pre-tax future earnings of capital (future savings).

Dr. Wood’s interest in Louis Kelso’s theory of binary economics is reflected through his work creating the OICs and efforts to advance economic and social justice. The former revealed the value of enabling people to earn an income through meaningful work and the latter of the transformative potential of capital ownership/income. Dr. Wood understood the economic potential of real capital ownership and that relying on wage income alone would be insufficient to address the roots of poverty in America. The video below shows Dr. Wood speaking about this idea (1:28) while we visited the Booker T. Washington High School in Houston in 2018.

During our early conversations, Dr. Wood explained how, in February of 1968, he made the case to Dr. King, Jr. that a Poor Peoples’ Campaign built on the “Why” of his Beloved Community concept, without the “How” embodied in Louis Kelso’s theory of binary economics, would mean that the promise of the campaign would remain unfulfilled. Dr. Wood’s underlying argument was that the Poor Peoples’ Campaign should be taken to Wall Street, rather than to Washington, to which Dr. King, Jr. apparently replied, “you are right, but we can’t do that now.” Dr. King’s assassination on April 4, 1968 effectively halted the integration of these ideas. This historic moment anchored our partnership and provided a clarity of purpose around reigniting Dr. Wood’s 1968 vision.

Today, the need for a reformulated Poor Peoples’ Campaign that helps build a new and regenerative economy cannot be more pressing. Few people earn enough to take care of themselves or their families. Labor, the main source of economic productiveness prior to the industrial revolution, has declined in relative productiveness as labor-displacing technology (think GenAI) advances and becomes hyper-productive in comparison to labor. These trends are driving the growth in inequality and the erosion in labor earning capacity, with the ownership of productive wealth being highly concentrated, and with most people owning little or nothing.

Dr. Wood envisioned a modern day Poor Peoples’ Campaign (what he called the Beloved Economy) built around the ideas of Dr. King, Jr. and Kelso. In the Beloved Economy, the ownership of capital―a critical and growing form of income―becomes more inclusive by using future capital earnings (future savings) to finance broadening capital acquisition to provide growing numbers of people with capital income. Dr. Wood knew that as production becomes ever more capital intensive, providing the poor with a capital ownership stake will be critical to broadly increasing purchasing power, reducing inequality, and advancing Dr. King, Jr’s notion of the Beloved Community.

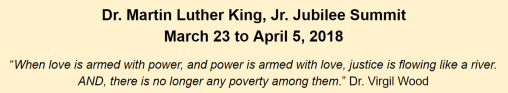

During his time with Virginia Tech, Dr. Wood led the creation of the Beloved Community Initiative (BCI) that established an essay contest (see the essay contest video and several photos from the award ceremony below) and hosted the MLK Jubilee Summit in 2018.

In that same year, he was invited to give the Virginia Tech Graduate School Commencement speech.

In an effort to capture some of Dr. Wood’s life experience, my colleague Prof. Sylvester Johnston interviewed Dr. Wood and his long-term friend Prof. Owen Cardwell (University of Lynchburg) in 2018 about their upbringing and work. The first 25 minutes of the video below, produced by Prof. Rachel Weaver, covers Dr. Wood’s early childhood, his time with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the economy of abundance, and more. In addition to this video, we decided to record an informal “In Conversation” series where Dr. Wood held discussions with his colleagues, including Prof. Cox, Prof. Cardwell , Dr. Hulbert, and Dr. Tasby and Dr. Smith. The complete set of recordings can be found on the Beloved Community Initiative YouTube channel.

During his visits to Virginia Tech, Dr. Wood always asked for opportunities to speak and engage with students, faculty, staff, and the local community. He had a unique ability to make people feel heard and left spaces filled with energy and opportunity.

Dr. Wood leaves behind a legacy that will continue to inspire future generations. In his own words, “the song has ended, but the melody lingers on.” It is now left to everyone who knew Dr. Wood to pick up and work with what he left behind to build the future we believe is possible. He was not just a leader but a beacon of hope, compassion, and purpose. His life reminds us that the pursuit of justice and equity is a journey worth dedicating everything to—and that even in our twilight years, we can still shine brightly.